What Estonians Say Can Sometimes Mean the Opposite

Text Stewart Johnson

Every language evolves over time, and Estonian is no different in this sense. What does make Estonian different, however, is the nuance involved in many of the words and expressions. Just as Michael Jackson once made the word bad mean good, until the name “Michael Jackson” itself became bad, so too does this colourful language speak with contradictions. This is a guide to navigating the pitfalls of comprehension when having a conversation with an Estonian.

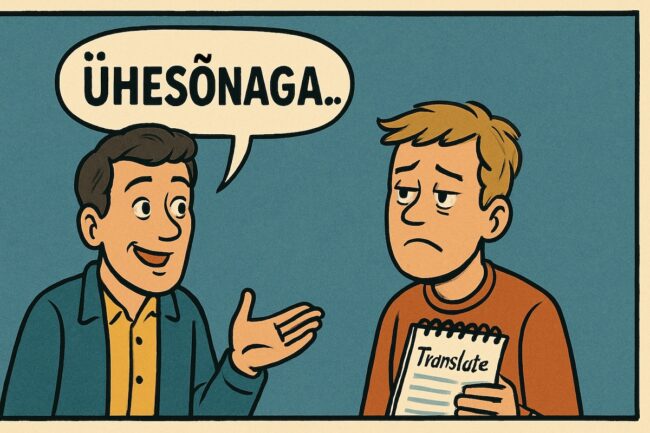

Estonians are known as a people of few words, meaning that every word spoken carries significance. Supposedly. That’s the stereotype. The reality is the opposite. For example take the word ühesõnaga, which means basically or in a nutshell, but quite literally translates to English as with one word. True to Estonian precision, the Estonian word for with one word is indeed one word. But when an Estonian says this in conversation, you need to be prepared for a lengthy explanation consisting of many dozens of words, and many dozens of minutes of listening.

Estonians also typically do not accept everything you say at face value automatically. They are logical, and they want proof. Once you have managed to convince them that you are telling the truth**, they will often say, “Issand jumal!” This saying expresses incredulity, even though they now believe you. Another contradiction here is that the term literally translates as Lord God, something most Estonians do not believe in. To summarise: Estonians will say something they don’t believe in to express that they believe you, even though what they now believe is unbelievable.

**Estonians by nature are sceptical, and for very good reasons. It doesn’t necessarily mean they are accusing you of lying. Sometimes you just need to repeat what you’re saying a couple times. Some people might think this means Estonians are slow to understand, but the truth is they are slow to trust a fact, or situation. For example, see this fictitious dialogue:

“I went to church last Sunday.”

—No, you didn’t.

“Yes, I did.”

—No, you didn’t.

“Yes, I did.”

—Issand jumal!

“That’s what I said when I got there.”

All languages also have filler words, or more colloquially, parasite words. Words that people use without thinking, and they can be difficult to purge from the speaker’s vocabulary. One example would be tähendab, which literally means this means, but in reality it means the speaker doesn’t like what they have already said, and they are now going to say it in a different way, and with more than one word.

Noh is a special case. This can be used as a general question meaning the speaker is impatient and wants an update. An Estonian father walks into his son’s room and wants to know if his homework has been finished. “Noh?”

When used as a statement however, it can still express a question. For example, this same Estonian father has a foreign friend visiting, and takes the friend on a tour of Tallinn’s Old Town. At one point, they enter one of the many famous churches in the Old Town, and the Estonian father sees several Estonian friends in the church, sitting and praying. The Estonian father will say simply, “Noh.” When the friends turn around, realising they’ve been caught red-handed, one of them exclaims, “Issand jumal!” (It should go without saying that none of the friends will say, “Hello, father!” while in this church.)

No vot is a popular expression that in English would mean there you go, or voilà. No vot stems from the Russian language, and if it’s used in the Riigikogu, Estonia’s parliament, it’s pronounced more like no vote. On the other hand, the Estonian jah means yes, but if an Estonian wants to say that they are tired of the current conversation, they will use a contradiction to agree with what you’re saying: “Nojah!”

In summary, and speaking in the first person now, I, as the author of this guide to having a conversation with Estonians, will tell the tale of how Estonians won’t always teach you the proper way to say something in their beautiful, mystical language. When I first started learning Estonian, I took a class. I asked the teacher how to say year, week, month, and so on. When I asked her how to say twelve months, she stood up straight, looked directly at me, and said slowly, with perfect pronunciation, “Please leave the classroom.”

A year later I was trying to rent an apartment, and the landlord asked me how long I would like the lease to be. I replied confidently, “Please leave the classroom.”

To learn more about this and similar topicsEstonia Estonian Culture Estonian Language Estonians