How memories of the past are affecting Estonia today

Text Antti Sarasmo Photo The Baltic Guide Archive/Hannu Lukkarinen

Tangible remnants of the past, such as statues and sites, have once again become a contentious issue in Estonia. This time, the debate revolves around monuments linked to the Second World War and the meanings ascribed to them.

In the centre of the winter capital of Otepää, there was a large park containing a Soviet soldiers’ burial ground. It was a hero’s cemetery, supposedly the resting place of the Soviet soldiers who had “liberated” Otepää. Similar cemeteries were found in the centre of nearly every significant settlement in Estonia.

The size of the cemetery in Otepää puzzled many since the hilly skiing town was far from any major route. The last major battle in the area had occurred in the 13th century, when German crusaders defeated pagan Estonians and captured the region’s largest ancient fortress. The Second World War’s battles had largely bypassed the challenging terrain of Otepää.

Eventually, suspicions prompted an investigation to confirm the cemetery’s extent. Ground-penetrating radar revealed no signs of any graves. No burial pits, no shallow field graves—nothing had ever been dug there. The land was undisturbed.

The fictitious cemetery’s monuments were subsequently removed, and the area reverted to a park. Back in the Soviet era, Otepää’s ambitious red leadership had created the hero’s cemetery to earn praise and recognition. For decades, flowers and wreaths were laid, speeches were made, and ceremonies held there. Early on, it was widely known that the entire cemetery was a staged fabrication.

Even more extreme than fabricated cemeteries are instances of body swaps. This year, soldiers buried in a wartime cemetery at Tehumardi on the island of Saaremaa were reinterred. A significant battle occurred there in 1944, as advancing Soviet forces sought to cut off retreating Germans. The clash was brutal, and Soviet soldiers were buried in a field cemetery that was later turned into a hero’s cemetery.

The hero’s cemetery was elaborate, featuring a monument of a broken sword surrounded by graves, each marked with fine headstones engraved with the names of the fallen. But when the cemetery was dismantled to move the remains to a regular graveyard, a surprise awaited: the graves contained bodies in hospital attire, not battlefield casualties. It appears the cemetery held soldiers who died in a field hospital, and the mass grave of those killed in battle remains undiscovered. The names on the headstones are equally uncertain—some might belong to those buried there, others to soldiers fallen elsewhere, or even to entirely fabricated individuals.

Such discoveries have come to light because Estonia’s Ministry of Defence now has a special department dedicated to respectfully dismantling Soviet-era ceremonial burial grounds and relocating the remains to proper cemeteries.

Narva’s Tank

Not all Russian-speaking residents in Estonia identify as Estonian-Russians; many see themselves as ordinary Russians living just across the border. Estonia has generally taken a permissive approach to these differing identities, rarely interfering with individuals’ self-perceptions. Major Soviet monuments were removed, and streets across the country reverted to their original names, but smaller relics were often left alone.

One such relic was the Narva tank. The T-34 tank had long been just a war memorial to local residents, causing no issues.

This changed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. By spring 2022, the tank had become political, with flowers and candles left at its base to express apparent support for Russia and its army.

The Ministry of the Interior informed Narva city officials that the monument had acquired a problematic new significance. They recommended moving the tank to a less visible location, such as the courtyard of Narva Castle. The city council formed a committee to deliberate, seemingly intending to prolong the process. However, the ministry did not wait beyond its set deadline. One summer morning, a transport truck, crane, and police officers arrived. The tank was taken to Tallinn and placed in the Estonian War Museum’s equipment hall.

The controversy didn’t end there. On “Victory Day” in 2023, the tank’s former location was covered in flowers. The Ministry of the Interior responded by announcing it would compulsorily purchase the site to erect a border surveillance camera tower. The compensation offered was 1,940 euros—a pointed reference to 1940, the year the Soviet Union occupied Estonia and abolished its independence.

History Returns

After the Cold War and the collapse of socialism, Estonia, having regained its independence, believed the era of historical falsification was over. No longer was there a need to march with flags on socialist holidays or praise the triumph of socialism.

It was assumed that the ideological clashes of the past had ended and that a unified historical narrative of Estonia and its diverse inhabitants would emerge, albeit with varying national perspectives. However, Russia’s attack on Ukraine shifted the atmosphere, reigniting the battle over historical truth.

The heroic cemeteries for Soviet soldiers from the late 1940s and the new political meanings attributed to older war monuments are part of the same story. The narrative of the “Great Patriotic War” is used to justify actions that Estonia sees as threats. As a result, Estonia takes a firm stance on commemorations of the “Great Patriotic War.”

“The Broken Finnish Bridge”

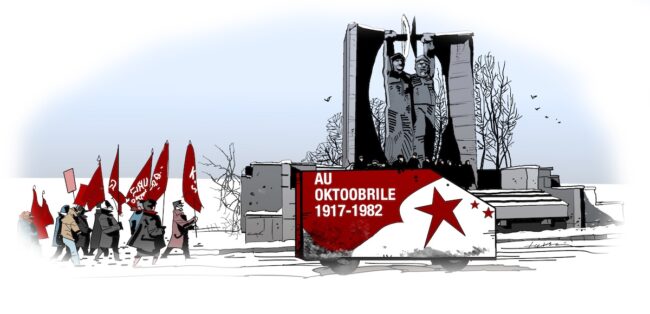

Remembrance can take many forms, as illustrated by the Maarjamäe Monument.

Located on a hill along the coast on the way from Tallinn to Pirita, the monument resembles an unfinished motorway bridge. It was nicknamed “The Broken Finnish Bridge” during the Soviet era, but its official name was “To Those Who Fought for Estonia’s Freedom.” After Estonia’s independence, the monument was deemed fitting enough to remain standing. Under Soviet rule, “freedom” referred to the Soviet Republic, but its meaning in independent Estonia has naturally changed.

Later, a corridor with black walls was added near the monument, engraved with the names of Estonian victims of communism.

Thus, the monument’s meaning was completely reversed. Originally built over a wartime German military cemetery to celebrate socialism’s victory, it now commemorates Estonian suffering and serves as a place to reflect on the nation’s history.

Places and monuments can acquire—or be given—new meanings. This is the crux of Estonia’s current struggle: a battle over the meanings and messages of memorial sites. History has returned, and the echoes of the past are shaping people’s understanding of the world today.

To learn more about this and similar topicsEstonian History and Identity Narva Tank Red Army Cemeteries in Estonia Soviet-Era Monuments Tehumardi War Graves Estonia WWII monuments in Estonia